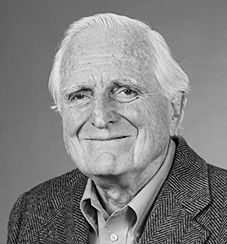

Doug Engelbart will be long and justifiably remembered as the inventor of the computer mouse, as a pioneer in the development of hypertext and for the December 9, 1968 “Mother of All Demos,” the first exhibition of integrated point-and-click, windows, hypertext, hyperlinking, word processing display editing and collaborative computing nearly three decades before such cyber-environments became the norm.

But, though he was inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame last year, Dr. Engelbart’s greatest contribution to society may not have been technological. The Internet pioneer’s greatest breakthrough may be to change how we think, how we learn and innovate, and how we collaborate.

Dr. Engelbart’s ideas have proved an inspiration to a wide swath of admirers and acolytes including his daughter, Christina, an assiduous guardian of her father’s legacy who runs the Doug Engelbart Institute.

Then there’s Adam Cheyer, co-founder of Siri (yes, that Siri) and founding member of Change.org, and Patricia Seybold, technology consultant and author of Outside Innovation; both found inspiration through their mentor Dr. Engelbart. Even President Obama has publicly recognized and praised the value of Dr. Engelbart’s philosophical breakthroughs.

The Uganda Rural Development Training Programme (URDT) is one place that beautifully exemplifies the ideas developed by Dr. Engelbart. Over the last 25 years, thousands of school girls have been taught to become agents of change, using the same approach developed Dr. Engelbart (http://bit.ly/1DXQ1Cd).

But it is Virginia Commonwealth University’s (VCU) vice provost for learning innovation and student success, Dr. Gardner Campbell, who is most active in bringing Dr. Engelbart’s thinking/learning/collaborating concepts into the environment most closely associated with augmenting human intellect: education. Last summer, Campbell and five other VCU faculty members presided over an innovative connectivist MOOC (massive open online course) based on a sophomore-level writing course.

The subject matter of Campbell’s pilot cMOOC – on conducting focused inquiry and research writing – its concept, design and curation, and its name are based on Engelbart’s learning and collaborative concept: “Thought Vectors in Concept Space.”

“We don’t think in scrolling pages or in paragraphs,” explains Christina. “Our minds dart around even when we’re thinking in a focused way. Our thoughts are vectors in that concept space – they collide together and create associations. They connect dots in novel ways, and that’s where breakthrough thinking comes from. It comes from our minds in a concept space, not a piece of paper.”

Campbell’s “Thought Vectors” course encouraged 120 students to pursue what he calls “trails of wonder, rigorously explored” – methods for mindful inquirers to emerge within an open creative space, then to rigorously explore that space.

Thought Vector Origins

Dr. Engelbart began pursuing the ideas behind thought vectors long before he had ever seen a computer. While a Navy radar technician in the Philippines in September 1945, he came across “As We May Think,” an Atlantic Monthly essay by Vannevar Bush, science advisor to President Franklin Roosevelt. In his essay, Bush called for “a new relationship between thinking man and the sum of our knowledge,” and imagined a kind of automated collective memory he dubbed the “Memex.”

Years later, working out the conceptual framework for the insights he would pursue throughout his life, Engelbart recalled Bush’s ideas. During an age in which computers filled a room, were controlled by punch cards and used for little more than as a giant calculator, Dr. Engelbart envisioned how these new machines could be used to create, access and share ideas and information. Taking Bush’s Memex to an entirely new level as he imagined the digital revolution to come, Dr. Engelbart laid out his manifesto for what he later dubbed ‘collective IQ’ by improving how we collectively develop, integrate and apply knowledge published in his foundational October 1962 paper, “Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework.”

“Doug’s essay touched every fiber of my being,” says Dr. Campbell, who came across the paper in 2004. “It validated my own quest for an ‘integrated domain’ as a teacher and scholar, even though my specialty had nothing to do with computer science. But more importantly, the essay lifted my eyes to even greater possibilities for augmenting intellect than I had imagined. Doug’s burning ambition, expressed so beautifully and powerfully in that 1962 essay, filled me with hope and determination that human capacity could grow and flourish in ways far beyond our current practices suggested.”

Dr. Engelbart himself used his thought vector concepts in his own work to think outside the box. “He focused on the research of improving capability, not on improving technology,” his daughter notes, “how capable we can be and how we employ that together. As we make leaps and bounds in our group practices, this informs where to take the tools.”

Thought Vectors in Action

Considering Engelbart’s influence, it’s no surprise that Campbell’s cMOOC was designed to train students to conceptualize their knowledge work as “thought vectors,” and to create and exploit a collective IQ within a shared “concept space.”

“Many strands of Doug’s thought inspired the design of the cMOOC,” explains Dr. Campbell. “We wanted students to see each other’s work products as a way of raising the collective IQ. The process was then recursive in that students would become aware that their collective IQ was increasing, which would then drive further refinement and improvement.”

Campbell and his VCU compatriots are not just teaching Engelbart’s insights; they are putting them to practice in their innovation approach. This includes: seeing the cMOOC as a research vehicle for exploring new frontiers in teaching and research; recruiting expedition-quality participants to co-design as well as team-teach the course; broadening the network of collaborators within and outside the University; and folding learnings into course design and into the way they continuously innovate the way they work together. Christina Engelbart teamed with Gardner to establish the first ever Engelbart Scholar Award in conjunction with the cMOOC.

Now Gardner’s team wants to further refine the cMOOC concept with a new version of the “Thought Vectors” course set to launch this fall, with different sets of students working in varying combinations of face-to-face or fully online environments, all doing their work in the same web-augmented “concept space.”

“We hope to learn some things about course modalities, and what approaches need to be adapted as those modalities change,” Dr. Campbell continues. “We want another version of Doug’s integrated domain, where sophisticated concepts are integrated with hunches and ‘cut-and-try.’ Like Doug, we ‘do not speak of isolated clever tricks that help in particular situations.’ Students have acquired lots of those strategies before they come to us, and unfortunately that learning has led them away from the deep and rewarding habits of inquiry and curiosity we hope the course can help to renew.”

Which modality approach ends up working the best will help Campbell perfect his cMOOC, and perhaps create a model for a more broadly applicable cMOOC framework. “Early results lead me to believe that we will eventually be able to build an inter-institutional network of thought vectors courses,” enthuses Dr. Campbell.

The spread of such thought-vector-based collective IQ experiments could be Dr. Engelbart’s greatest legacy.